Overcoming Energy Crises: Japan's Path to a Carbon-Neutral Future

5/15 2024

Author: Satoshi Honma

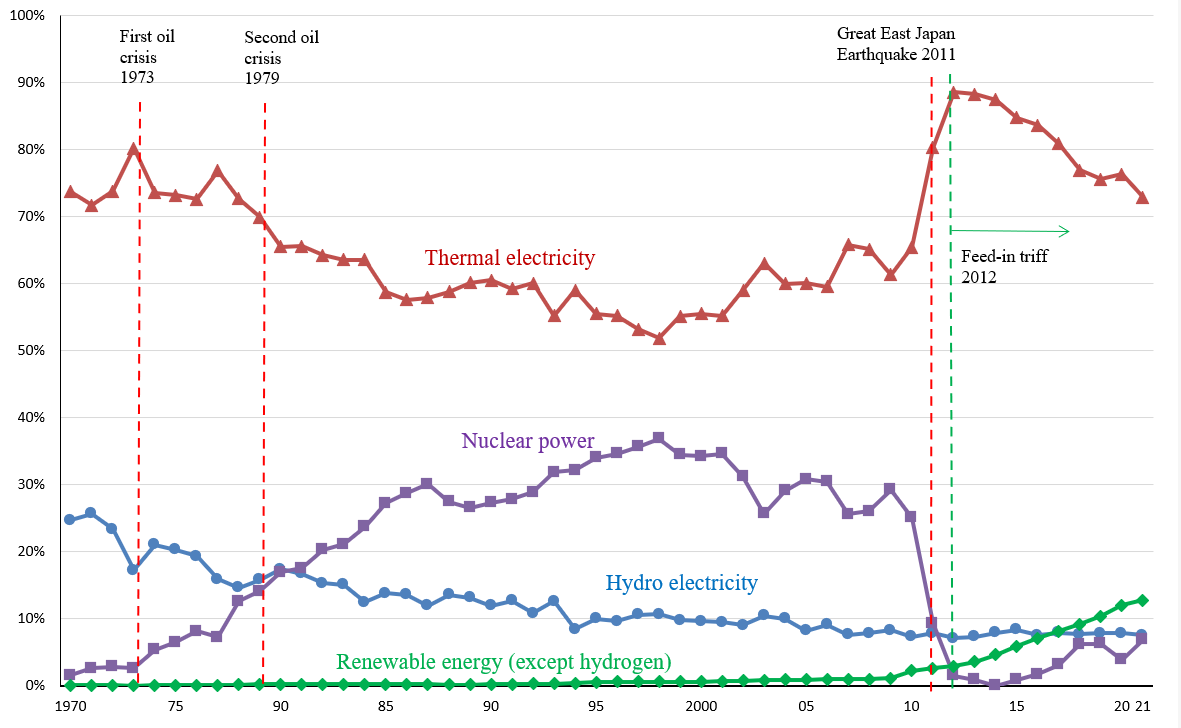

The first oil crisis in 1973 dealt a severe blow to the Japanese economy. In response, Japan took steps to reduce its dependence on oil and diversify its energy mix. Natural gas, coal, and nuclear power were developed as alternatives. The share of thermal power generation declined steadily from 80.2% in 1973 to 65.5% in 1980 and reached a minimum of 51.9% in 1998 (Fig. 1). This decrease was primarily offset by an increase in nuclear power generation, which was actively developed as alternative to fossil fuels. It is noteworthy that in 1974, the Sunshine Project was launched to promote the development of technologies for alternative energy sources such as solar, geothermal, coal, and hydrogen (Despite this initiative, the share of renewable energy remained below 1% until the early 2000s).

Source:Prepared by the author based on the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry's Energy White Paper 2023.

The Great East Japan Earthquake in March 2011 and the subsequent accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant dealt a severe blow to public trust in nuclear energy as a safe and reliable power source. Renewable energy has become more important than ever in terms of energy self-sufficiency and cleanliness. The 2012 feed-in tariff scheme drastically expanded the share of renewables in electricity generation from 2.6% in 2011 to 12.8% in 2021. Meanwhile, nuclear regulations and inspections were thoroughly overhauled (see Risk Management: Relationship between facility managers and regulators , Author: Hideka Morimoto, May 1, 2024).

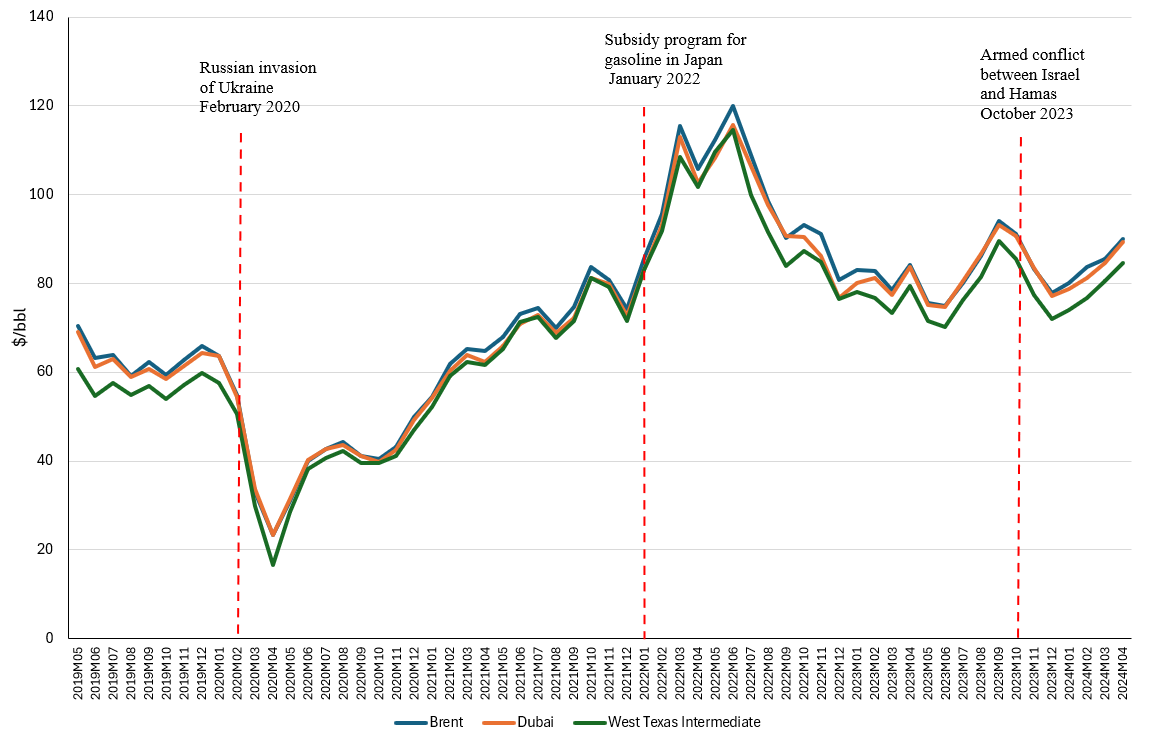

Source: Prepared by the author based on data from the World Bank Commodity Markets

( https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/commodity-markets )

Japan now faces soaring fossil fuel prices and supply instability triggered by Russia's invasion of Ukraine. In June 2022, the prices of WTI, Brent, and Dubai crude reached $114.59, $120.08, and $115.73 per barrel, respectively (Fig. 2). Heightened geopolitical risks in the Middle East further threaten supply stability.

As is well known, Japan has pledged to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 46% from 2013 levels by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Effective implementation of new energy policies is key to meeting these targets.

In January 2022, nevertheless, the Japanese government began providing subsidies to curb the surge in gasoline prices. These subsidies, which were supposed to end in April this year, have been extended for the seventh time. Subsidies for fossil fuels undoubtedly run counter to the path towards decarbonization.

As noted in a previous Chart of the Week (see Japan’s Gasoline Subsidy Policies Contrary to Decarbonization, Author: Satoshi Honma, June 17, 2022), in the absence of subsidies, elevated gasoline prices could have induced a partial shift in consumers' preferred modes of transportation, encouraging a transition from personal automobiles to alternatives such as bicycles and public transport. Moreover, higher gasoline costs may have incentivized consumers to actively seek out and adopt more fuel-efficient or alternative energy vehicles, such as hybrids, plug-in hybrids, and electric vehicles. This shift in consumer preferences and behavior, driven by the economic pressures of increased gasoline prices, could potentially contribute to reduced gasoline consumption and the adoption of more sustainable transportation practices.

Japanese energy policy has historically been revised after each crisis as policymakers' and the public's sense of urgency rises. The current energy crisis should prompt Japan to launch new energy policies with a focus on achieving carbon neutrality. As a first step, the Japanese government should not extend the gasoline subsidy any further.