Reducing VOCs emissions as a countermeasure for Suspended Particulate Matter (SPM)

2/15 2025

Author: Osami Sagisaka

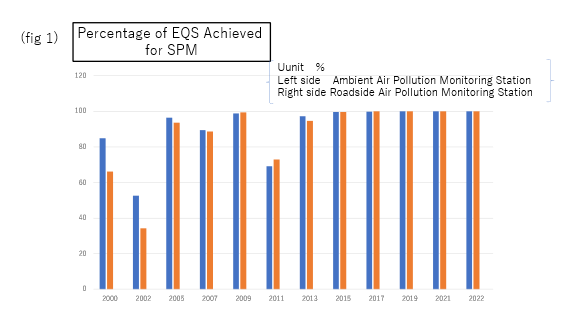

Since the 1960s, sulfur oxides (SOX) and nitrogen oxides (NOX) have been the main causes of air pollution. Strict regulations on pollutant emissions from factories and emissions from automobiles have led to improvements in these pollutants, and by the early 2000s, EQS were achieved at most monitoring stations. (For NOX, however, the percentage of EQS achieved of roadside air pollution monitoring stations was still insufficient.) For SPM, however, the percentage of EQS achieved remained low, although it varied from year to year (fig. 1). Therefore, in the early 2000s, SPM countermeasures were a priority issue for air quality preservation.

Measures related to SPM have been addressed in the past through restrictions on pollutant emissions from factories and automobile emissions. And the explanation for the lack of improvement in the percentage of EQS achieved has been that it may be due to the influence of Dust and Sandstorms(DSS) from the continent. However, a closer examination of the sources of SPM reveals that a significant proportion of SPM come from sources other than pollutant emissions from factories and automobile emissions. One such source is Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs).

VOCs have been monitored for their emissions in the past, with the possibility that they may be a causative agent of photochemical smog. On the other hand, as scientific knowledge has accumulated, it has also become clear that VOCs change in the atmosphere and become a causative agent of SPM. Regulations on VOCs were already in place in the U.S. and Europe. In Japan, studies to control anthropogenic emissions of VOCs were initiated in 2004.

In studying control measures, a number of industries that emit VOCs into the atmosphere were examined. Until now, Japanese air pollution control measures, such as those for pollutant emissions from factories, have been based on the regulation of emissions from factory outlets. However, some VOCs were emitted from production processes in printing factories, some leaked from oil tanks, and some came from outdoor works, such as painting in shipbuilding companies, making it impossible to determine the target of VOCs control. There was also criticism that regulating only those industries with emission outlets was not sufficient, and that it violated the principle of “equality” when regulating pollution.

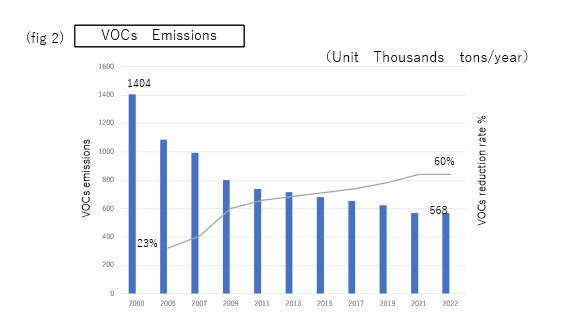

The method developed in response was the so-called “Best Mix” approach. Japan's Basic Environmental Plan covers a variety of environmental policy approaches. Among them is one that encourages voluntary efforts. In other words, the combination of “regulatory methods” and “voluntary efforts” will avoid the criticism that only certain industries are subject to regulation. The regulatory approach should be applied to emissions from outlets, while the voluntary approach should be applied to other areas. For example, to prevent leaks from oil tanks, tanks should be equipped with floating roofs, and to prevent emissions from outdoor operations, low-VOCs paints should be used. If sufficient emission reductions (40% reduction compared to FY2012) are not achieved after five years, then the measures will be further strengthened.

The revised law was promulgated in May 2005 and went into effect in June 2006. To date, businesses have made efforts to reduce VOCs emissions beyond the planned level (40% reduction from the base year) (fig. 2)

In any case, the percentage of EQS achieved since FY2015 is almost 100% (fig. 1); although the impact of DSS has been frequently reported since FY2015, the achievement of EQS is presumed to be due to lower background concentrations of SPM. It is believed that the “Best Mix” approach to VOCs control has been successful.