Mega-mining impact in Mongolia’s pastoral commons

1/15 2025

Author: Troy Sternberg

Research focused on three ‘significant state resources’ – Oyu Tolgoi, Tavan Tolgoi and Gurvantes mines extracting copper, coal and gold. From nascent exploration in 2003 to producing ~50% of government revenue in 2022, the mines are economic drivers and environmental disruptors. Whilst debates in the capital discuss public engagement, corporate social responsibility and meeting the SDGs (e.g. 6, 8, 13, 15), communities focus on complaints, pollution and negative livelihood impacts. Today technologies enable in-depth knowledge and analysis to inform citizens and governance at local and national levels. Remote sensing is an excellent tool to assess the Gobi Desert, document land cover change and quantify the impact of resource extraction on traditional pastoral lands. Matched with herder surveys, research in 2024 identified the vast footprint of mining in the Gobi.

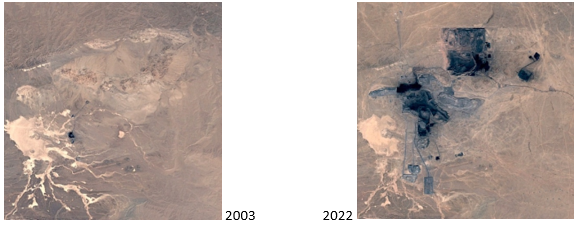

Using satellite imagery - MODIS-NDVI, 30 metre resolution - we evaluated land cover change at 0-5km, 5-10km, and 10-20km zones around each mine. Analysis identified a massive expansion of mining land take at each site, with increases of 692%, 3132% and 3638%. The largest, Tavan Tolgoi, now covers 450 km2 at a single mine (an area larger than Osaka or Nagoya). There was a parallel decrease in vegetation at zones closer to the mines. Additional land beyond mine sites was taken for air strips, quarries, roads, pipelines and similar infrastructure. Fencing and exclusion zones further reduced pasture and fragmented land. The outcome was decreased pastoralist access to customary communal environments.

Though without technical data, herders identified reduced pasture and access to water from their personal experience. Despite numerous complaints, little had changed over two decades, nor had mining contributed positively to the communities. Herders aware of the SDGs (28%) all expressed the programme had no benefit for their lives and work. A typical response was ‘they talk about the Sustainable Development Goals, but we don’t see any of that support reaching us. It’s like these initiatives exist in another world, far from our reality’ (Zaya, 33).

Investigating three mega-mines identified the two-decade degradation and loss of pasture resources. Since 2003 the sites saw vast mining expansion into communal lands accompanied by detrimental environmental practices and conditions. Explained or justified by global initiatives such as the SDGs, local communities experience a different reality. Once mine sites are defined, capitalised and developed, communal land decreases and fragments (Figure 1, 2).