Relative Poverty in Advanced Economies:

The Role of Government for Social Spending in Poverty Reduction

10/15 2025

Author: Naoto Yoshikawa

This note considers the persistence of poverty in developed nations within the framework of the first Sustainable Development Goal (SDG): “End poverty in all its forms everywhere.” Public discourse on poverty eradication often emphasizes “absolute poverty,” conventionally defined as living on less than $2.15 per day and primarily associated with developing countries. Yet advanced economies also confront serious poverty, particularly in the form of “relative poverty.” Relative poverty refers to individuals whose income falls below half of the national median household income (OECD 2025b). In Japan, for example, the median income in 2021 was 2.51 million yen, which establishes a relative poverty threshold of 1.27 million yen (MHLW 2023). Falling below this threshold indicates a state of severe hardship. Relative poverty is widespread in developed nations, with rates of 17.8 percent in Israel, 15.4 percent in Japan, 15.2 percent in the United States, 14.8 percent in South Korea, and 14.4 percent in Spain (OECD 2025/b). These figures underscore that poverty is not confined to developing economies but persists as a structural challenge in wealthy societies.

A central question is the role governments should play in alleviating relative poverty. Across the OECD, between 15 percent and more than 30 percent of national budgets are typically devoted to social expenditures aimed at improving citizens’ welfare (OECD 2025/a). Such expenditures are commonly understood as indicators of redistributive policy. Regression analysis of data from 33 OECD countries demonstrates that higher levels of social spending tend to be associated with lower relative poverty rates. However, the coefficient of determination was only 0.157 (R²), indicating that social spending alone provides limited explanatory power (OECD 2025b; OECD 2024). Other factors, including demographic aging, disposable income levels, and educational investment, were also considered but proved insufficient in explaining cross-national variation.

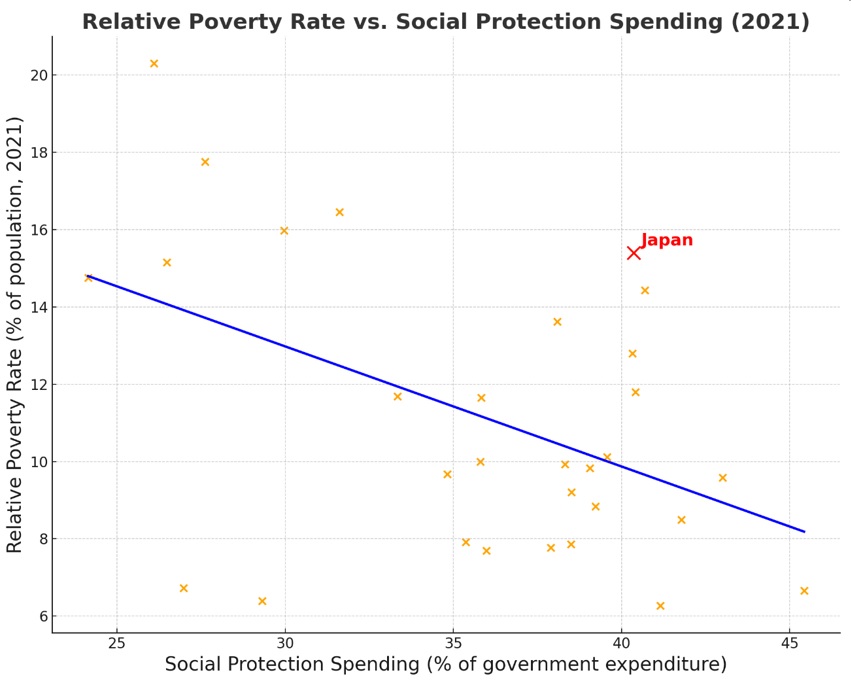

To achieve greater analytical precision, the study focused on social protection spending—direct support for vulnerable groups, including pensions, healthcare, child allowances, and housing subsidies. Regression analysis of 30 OECD countries in 2021 revealed a negative correlation between relative poverty rates and social protection spending (measured as a percentage of total government expenditure), which is shown in the figure below.

The explanatory power modestly improved, with the coefficient of determination rising to 0.221 (R²). The findings suggest that each one-percentage-point increase in social protection spending corresponds, on average, to a 0.31 percentage-point reduction in relative poverty.

In this analysis, country-level comparisons underline this pattern. France, Germany, Denmark, and Sweden—Northern and Western European nations—allocate relatively high proportions of expenditure to social protection and maintain comparatively low poverty rates. By contrast, the United States, Israel, and Costa Rica devote smaller shares to social protection and face higher poverty levels. Japan stands out as an anomaly: despite relatively high social protection spending, its relative poverty rate exceeds the OECD average and borders on statistical outlier status. This discrepancy suggests that nearly 80 percent of explanatory factors remain unaccounted for by current models, pointing to deeper structural issues such as Japan’s segmented labor market, the prevalence of non-regular employment, and shortcomings in family policy.

Conclusion:

The analysis confirms that social protection spending exerts a significant, though not decisive, effect on reducing relative poverty in advanced economies. The Japanese case illustrates the limitations of relying solely on fiscal investment. Sustainable poverty reduction in developed nations requires comprehensive strategies that integrate redistributive policies with reforms in labor markets, educational systems, and family support structures. Ultimately, the persistence of relative poverty in advanced economies underscores the importance of multidimensional approaches. Governments must reinforce redistributive functions while simultaneously addressing structural and institutional challenges. Only through such integrated strategies can societies move closer to realizing the SDG mandate of ending poverty in all its forms.

Note: All regression analyses use 2021 data, the latest available.

References

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (MHLW) (2023) ‘II Kakusyu Setai no Shotokutou no Jokyo (Income and Socioeconomic Conditions of Various Households)’ “Kokumim Seikatsu Kisochosa no Gaikyo (Overview of the Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions).”https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa23/dl/03.pdf (accessed 4/10/2025).

OECD (2024) ‘Social expenditure aggregates’ “OECD Data Explore” https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?fs[0]=Topic%2C1%7CSociety%23SOC%23%7CSocial%20policy%23SOC_PRO%23&pg=0&fc=Topic&bp

=true&snb=12&df[ds]=dsDisseminateFinalDMZ&df[id]=DSD_SOCX_AGG%40DF_SOCX_AGG&df[ag]

=OECD.ELS.SPD&df[vs]=1.0&dq=.A..PT_B1GQ.ES20_30%2BES50%2BES40%2BES10._T._T._Z&pd=

%2C&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false&vw=tb&lb=bt (accessed 4/10/2025).

OECD/a (2025) ‘Social spending-Social expenditure includes cash benefits, in-kind goods and services, and tax breaks with a social purpose: Indicator.’ https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/social-spending.html (accessed 4/10/2025).

OECD/b (2025) ‘Poverty Rate- Poverty rate is the ratio of the population whose income falls below the poverty line: Indicator.’ https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/poverty-rate.html (accessed 4/10/2025)

Our World in Data (2025) ‘Social protection spending as share of total government spending: OECD’ https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/share-social-protection-in-government-exp-oecd (accessed 4/10/2025).