Water Under Pressure: Circularity for Sustainable Growth

9/1 2025

Author: Nawazish Mirza

Water is no longer an invisible input. For industries worldwide, it has become a strategic constraint. Rising demand, climate volatility, and regulatory pressure are reshaping how firms think about water. The linear model of withdrawal, use, and discharge is proving untenable. In its place, a circular water economy, where water is recycled, reused, and replenished, is emerging as both an ecological necessity and a marker of competitiveness (Mirza et al., 2024). The scale of the challenge is evident. Industry already consumes nearly one-fifth of the world’s freshwater, and that share is set to rise sharply as manufacturing, energy, and food systems expand. What was once a distant risk has become a lived reality. Droughts in Europe, water stress in Asia, and declining aquifers in North America are disrupting production lines and driving costs upward. Scarcity is no longer a scenario on the horizon; it is shaping business decisions today.

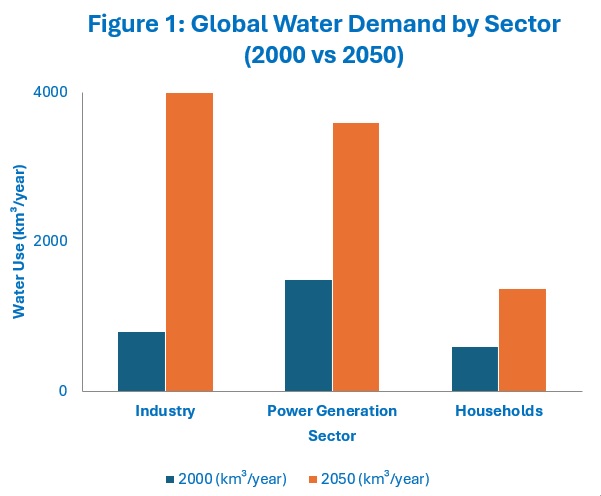

Figure 1 illustrates the magnitude of this shift. Industrial demand is projected to grow fivefold by mid-century, while power generation and households also record steep increases. The trend highlights why circular approaches are no longer optional. If firms continue to rely on linear consumption, the gap between demand and available supply will widen beyond what most regions can sustain.

Regulatory and financial signals are reinforcing this shift. The European Union has tightened its standards for water reuse, while Japan has promoted industrial recycling in response to its limited freshwater endowment. At the same time, investors are beginning to factor water risks into ESG assessments, placing reputational and financial pressure on firms. The response is visible in sectors that have long been associated with heavy water use. Beverage companies, often criticized for their footprint, are now experimenting with “net positive” programs that aim to replenish more than they consume.

Other sectors are pushing the boundaries of technological innovation. Semiconductor manufacturers in Taiwan, confronted with acute shortages, have adopted advanced recycling to secure their supply. Textile clusters in India are implementing “zero liquid discharge” systems that treat effluent and reuse it in their production processes. Singapore’s NEWater program demonstrates how governance and technology can make reclaimed water acceptable for industrial use. Consequently, circularity is becoming an operational reality, albeit at an uneven pace of adoption, as multinationals advance while smaller firms struggle to catch up.

Scaling these practices depends heavily on policy frameworks. Standards that clarify water quality requirements provide certainty, and fiscal incentives help offset the upfront costs of treatment systems. Equally important is the polluter-pays principle, which discourages wasteful discharge and rewards efficiency. Collaboration also matters, and shared facilities in industrial parks can help reduce costs, while municipal partnerships enable the integration of urban and industrial water cycles. Transparency is another pillar. Initiatives such as the CEO Water Mandate and the Science-Based Targets for Water are emerging as reference points.

Despite progress, barriers remain formidable. Advanced treatment systems are capital-intensive, leaving SMEs at a disadvantage (Zhu et al., 2023). Technical expertise is unevenly distributed. Public perceptions of reused water, particularly in the food and beverage industry, continue to pose a significant hurdle. These concerns explain why adoption has been patchy. Yet the upside is equally evident. Firms that invest in circular water systems report long-term savings on water bills and greater resilience against supply shocks. In markets where consumers and investors are increasingly aware of environmental performance, water efficiency enhances credibility and brand strength.

The broader context is sobering. The World Bank warns that by 2030, global water demand is likely to exceed supply by 40% if current patterns persist. Industry cannot shield itself from this imbalance. Circular water use should therefore be seen as risk management and strategic foresight as much as environmental responsibility. Policymakers and firms alike face three priorities. First, create incentives and standards that make reuse the rule rather than the exception. Second, strengthen corporate disclosure so that genuine progress can be distinguished from symbolic gestures. Third, build regional collaboration, particularly in Asia, where demand is climbing fastest under conditions of acute stress.

None of these steps is straightforward. They require striking a balance between innovation and regulation, as well as ambition and public trust. The broader trajectory of water use is clear, and its progress will determine how industries adapt to the challenges of resilience and long-term competitiveness.

References

Mirza, N., Umar, M., Sbia, R., & Jasmina, M. (2024). The impact of blue and green lending on credit portfolios: a commercial banking perspective. Review of Accounting and Finance, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/RAF-11-2023-0389/FULL/PDF

Zhu, B., Liang, C., Mirza, N., & Umar, M. (2023). What drives gearing in early-stage firms? Evidence from blue economy startups. Journal of Business Research, 161, 113840. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBUSRES.2023.113840